By Ron Jantz

reprinted with his permission

If you read my writings, my Ron’s Rambles or The People I Meet, you know I’m always in search of the ordinary person doing something extraordinary.

Tonight’s person may not be ordinary but he certainly accomplished something extraordinary.

First things first. My conversation with Eric Heiden doesn’t happen without the help of my friend Katie Marquard who skated for the United States in the 1984 and 1988 Winter Olympics and later was the Executive Director of US Speedskating.

Thank you Katie.

Now to my story.

****************************

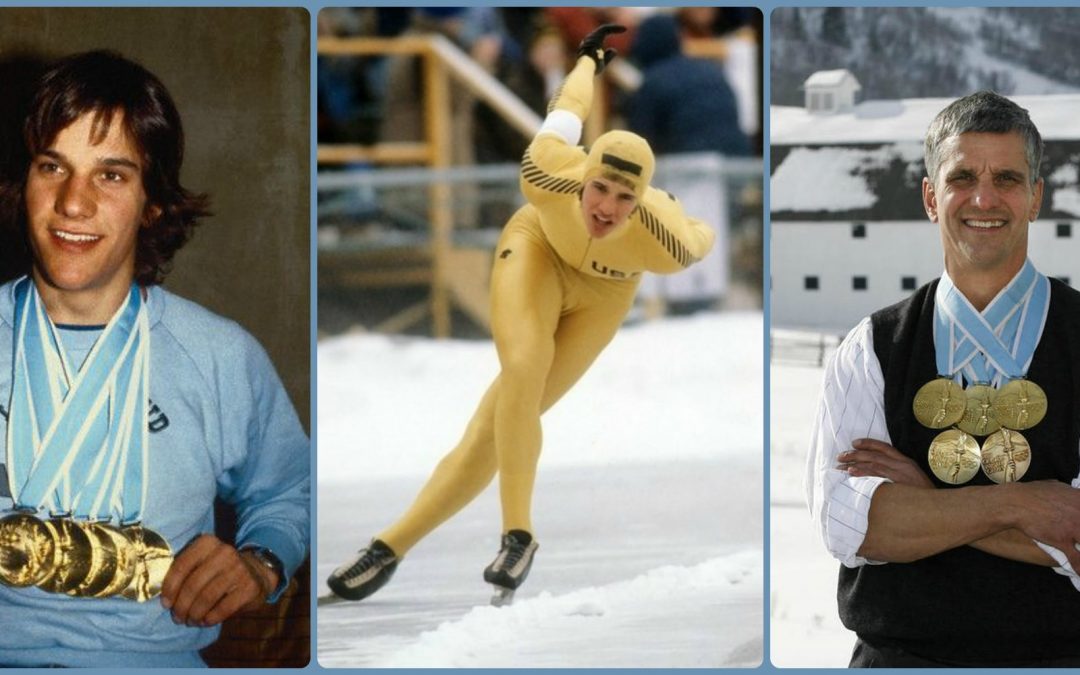

Forty years ago today, on the 23rd day of February in Lake Placid, New York, the man in the picture won his 5th gold medal in one Olympic Games. No winter athlete had ever done that and not one has done it since. He is the greatest speed skater in history. He not only won five golds, he set Olympic records in all five events and a world record in one during the 1980 games.

He was the living and breathing magical combination of a sprinter and a marathoner driven by the same set of lungs and legs and determination.

Some consider him one of the greatest athletes of all time.

The man is of course, Eric Heiden.

I talked to Eric on Saturday.

Where do you start with Eric Heiden?

“I’d like to focus on one thing,” I said to him as our phone conversation began. “I’d like to talk about the 10,000 meter skate, your fifth gold medal. The skate that made you a legend.”

There was a slight chuckle.

“I’m hearing they’re thinking about yanking the 10,000 meter out of speed skating,” Heiden said to me. “Why?” I wondered. “They think it’s hard for the public to watch, “he said. “Boring. 25 laps.”

There was nothing boring about Heiden’s 10,000 and the story leading up to it starts with hockey skates.

The cold streets of Lake Placid were warmed by the energy of a hockey team on the brink of turning the world upside down. “I was going to as many of the games as I could,” Heiden told me regarding the team that made us all believe in miracles. He knew two of the players on the United States hockey team. “I had played age group hockey with Mark Johnson and Bob Suter in Madison (Wisconsin) when we were kids.” Suter was a defensemen for the team and Johnson was about to have the kind of night that etches your name in stone.

It was February 22nd, the eve before Heiden’s 10,000 meter race.

“It was getting harder and harder to get a ticket to the hockey games,” Heiden said to me. “You know, they kept winning and more and more people were coming.” Heiden was able to secure a pass though.

The game was played in the early evening, 5 o’clock.

“It was a great game to watch,” he told me in his understated way. Johnson, his youth hockey friend, had scored two goals and the United States beat the Russians 4-3. Time has turned that game into the greatest accomplishment in sport but you could make a strong argument that Heiden’s accomplishment was just as great.

As the victory celebration spilled out of the arena and into the simple streets of Lake Placid, Heiden was in a van with other athletes on their way back to the Olympic Village to go to bed. This wouldn’t be just another night’s rest though.

Heiden would go to bed with a thought in his head that no athlete in the history of the Winter Games has ever had to sleep on.

An opportunity to win his fifth gold medal. Was it on his mind?

“Not right away,” he told me. “We were all just pumped and wondering how we were going to get tickets for Saturday’s game (the gold medal game),” he said laughing.

I wondered what kind of bed the young man, who was about to become a legend, was going back to fall asleep in. “A trailer,” Heiden said. Lake Placid struggled to have enough rooms for all the athletes so they brought in big trailers and set them up in the Olympic Village. “What kind of trailer? Was it special? Painted red, white and blue with the Olympic logo on it?” I asked. “Just trailers,” Heiden said with a voice that seemed like a shrug, “like you’d see at a construction site, like they found em and rented em. But, they did have their own fridge and bathroom, which was nice.”

It was my turn to laugh.

The trailers housed eight people with a divider down the middle. “There were four of us to a side,” Heiden said, “but we each had our own room.”

Heiden got to bed between 10 and 11 that night. “I usually toss and turn and don’t get much sleep the night before a race,” he told me. With that said, consider Heiden’s unprecedented chase of five gold medals had started with the 500m race on February 15th and was followed by the 5,000m on the 16th, the 1,000m on the 19th and the 1,500m on the 21st. By the time his head hit the pillow on the evening of the 22nd, not even the magnitude of the moment that waited for him when he woke could keep him from sleeping. “I was getting mentally exhausted in the days leading up to that (10,000m) race. It (lack of sleep) kind of caught up to me.”

Heiden overslept. The next thing he remembers was a pounding on his trailer room door. “It was Dianne,” he told me. Dianne Holum was Heiden’s coach. “She’s pounding on my door and saying Eric, Eric are you in there?”

He was but he was still sleeping.

“I don’t know,” he continued, “either my alarm clock didn’t go off or I didn’t hear it.” In my head – as this conversation is unfolding – I’m thinking can you imagine in our hyper-controlled sports environment today – if an athlete of his stature was about to complete what he was about to complete – he’d have at least a dozen people on the clock to make sure he got up when the clock said it was time to get up. So, I asked him…

“What kind of alarm clock did you have in your trailer? Was it one from home?” “No,” he said in a tone that still sounded hazy about the moment. “It was something from the swag stuff we got in a bag from the Olympics. You had to know what buttons to push, I guess.”

Heiden’s coach got him up. “I ran to the cafeteria and grabbed a couple of pieces of bread, store bought, cheap wheat bread to eat. I knew though that whatever I ate at that point wasn’t going to make a difference.”

As you can imagine, Heiden was very particular about his pre-race routine. It had to be the same, every time. On the morning of the biggest race of his life though, it would have to be different. “I was a little stressed,” he told me in his understated way, “but you gotta get it out of your mind. I had a very set routine that would take two hours but I had to abbreviate it.” I asked him how his routine would typically play out? “I always started with a run,” he answered. “Then, I’d stretch and then I’d go on the ice for 20 to 30 minutes. I’d go back inside and sharpen my skates after that and then return to the ice maybe five to ten minutes before it was time for me to race.”

The time spent sharpening his skates was the most consuming of his routine. “If I did a good job of preparing my skates,” he said, “it would take me 45 minutes.”

“Did you sharpen your skates?” I asked. “Yea, either me or my Dad,” he said. “Did you trust anyone else to sharpen your skates?” I continued. “No,” was his quick response and then he laughed. “I was pretty particular.”

“Why would you not go back onto the ice until five or ten minutes before your race?” I asked. “I didn’t want to lose an edge (sharpness of his skates) or risk getting a little dirt on the edges.”

The little things.

Heiden had been preparing for this moment his entire life, even if he never fully knew it.

Heiden grew up in Madison, Wisconsin. His grandfather was the hockey coach at the University of Wisconsin and his grandparents lived on a lake. “They always made sure there was a spot cleared for us to skate,” he told me in reflection.

Heiden thinks he probably first tried to skate as a two year old but he clearly remembers his first “marked” duty. “I started at the Madison Figure Skating Club,” he said. Heiden was five years old. “We skated on Sunday nights and The Wizard of Oz would be on television on Sunday evenings and I’d miss it. It was always a bummer,” he said in a tone that made me feel he had a childlike look in his eyes as he spoke of the memory. “Back then, the Wizard of Oz was a special event.”

We both laughed at “special event.”

Forty years ago today, that 10,000 meter race was a special event. Heiden was 21 years old. By the time he stepped on the ice that morning and readied himself to race, he had already won four golds in seven days in disciplines that ranged from a short sprint to now the marathon of speed skating. There was no one in the world that could do what Heiden was capable of doing.

There was no one with his range. But, he still had to prove it.

The last time an American had won gold in the 10,000 was in 1932 when Irving Jaffee won. The games of 32’ were also held in Lake Placid. Since that time, that distance in speed skating was dominated by Norwegians and Swedes.

The race was set to start at 9:30 in the morning and considering the way Heiden’s day started you could understand if he was even a slight bit distracted. Plus, the weight of the moment was unlike any winter athlete, speed skater or not, had ever experienced. I asked him about his mental approach. Did he try and convince himself this was just another race or not? “You can get pretty compartmentalized with your mind,” he said. “You don’t pay attention to the crowd. You don’t pay attention to the situation (chance for a 5th gold). That’s what makes good guys good,” he said matter of factly to me. “They can turn it all off.”

And, Heiden did.

The temperature was “in the teens or low 20s,” Heiden said as our discussion continued while adding a reminder that he was wearing a very thin, skin tight suit. “It wasn’t too cold,” was his comment. I laughed and responded, “said like only a guy who grew up in Wisconsin could say.”

Twenty five skaters would compete in the race. They would go off in pairs of two. Heiden was slotted in the second pair. He was matched with the reigning world record holder Viktor Lyoskin of Russia.

The Russian went out fast. “He took off,” Heiden said of Lyoskin. “I was getting my ass kicked. He was 100 meters ahead of me after 10 laps and I couldn’t imagine going any harder. I started to get concerned. I started looking over at my coach and she assured me that my times were going according to the plan we had laid out.”

Heiden trusted his coach. Trusted his training. Trusted his legs.

Heiden’s thighs were nearly as big as his waist. His waist was 32 inches and his thighs were 27. “I had big legs,” he said when I asked him how big. “I needed 38 inch waist pants to accomodate my legs.”

Heiden caught the Russian about halfway through the race and put him in his rear view mirror forever. “When did you start to feel good about the race? When did you start to feel like you were going to win the gold medal?” I asked. “Probably with five laps to go you start realizing there is a light at the end of the tunnel and you feel motivated. My lap times were good. I felt confident but you never know because there are guys who gotta skate after you,” he answered, “and sometimes you are so tired

you can’t….

And then he trailed off.

“Can’t what?” I asked. “You can’t raise your arms when you cross the finish line. Sometimes, it’s so hard to just stand.”

Heiden crossed the finish in 14:28.13 and set a new world record beating the old one by 6.2 seconds. He shattered the Olympic record by 22.46. Twenty one skaters went after Heiden that morning and no one came close to his time. The silver medalist was 7.90 seconds off and Lyoskin finished 23.59 back.

As we talked on Saturday, I wondered how the years had shaped it all for him.

“I find it fascinating,” he said, now 61 years old, “to run the table in any sport, I look at it as an outstanding athletic accomplishment.”

And…

“At the climax of my career, I skated four perfect races leading up to the 10,000 and then to win (at that distance) and it’s my opinion the 10,000 is the true test of the best skater because of all the time you have to put in, all the laps, the mental strength, how hard do you push, all of that and to win that race to finish it all, well, that’s the icing on the cake.”

Ice.

Nice.

Thanks Eric. Thanks for the conversation. I am very grateful for your time.